気候変動 - 待ったなしの地球温暖化対策(第3回)

パート3 脱炭素化への道–IEAによる「2050年までにネットゼロ」レポートの要約

毎週異常気象のニュースを耳にしない日はありません。 このような異常気象と気候変動の関連がないとは言えなくなっています。なぜならば異常気象の頻発が自然現象を上回り、CO2濃度が上昇した場合のモデル化されたシナリオの予測とぴったり一致するためです。

そして、CO2排出量はさらに加速し続けています。 国連によると、世界ではいまだに約7億8900万人が電気を利用出来ずにいます。 国際エネルギー機関(IEA)は、2050年には電力需要が現在の2.5倍になると予測しており、さらに数億人の人々が電力不足に悩まされることになるでしょう。1

私たちが直面する未曾有の課題と、気候変動による深刻な影響を回避するためのわずかな機会を考慮して、科学者達はさまざまなCO2濃度による気候変動の影響だけでなく、今世紀中の地球平均気温暖化を2°C未満に抑える可能性が比較的高いと考えられる排出シナリオのモデル化に精力的に取り組んでいます。 一般的に温室効果ガスの総排出量が2020年から2030年頃にピークに達し、2070年頃には世界全体で急速にゼロにするシナリオが提示されています。このようなシナリオを達成出来ない場合には、気候変動の影響、緩和策の必要性と関連コストの両面においてさまざまな影響をもたらします。

これらのシナリオは、私たちに提示される選択肢の基礎となりまた、政策決定に影響を与えるため、脱炭素化の道筋や私たちが直面する選択肢と、トレードオフを理解するのに役立ちます。 そこで本ブログではシナリオのポイントとモデルの限界を簡単に説明した後、脱炭素化に向けて「最も技術的に実現可能で、費用効果が高く、社会的に受け入れられる」道筋を提示しているとされ、影響力を持つIEAが最近発表した「ネット・ゼロレポート」に焦点を当てます。

国や企業がネットゼロの目標を導入する流れの中で、これが何を意味するのかについても触れますが、懸念すべき点と楽観する点の両方があります。 悪いニュースとしては、多くのネットゼロの宣言が、一時的なものに過ぎない森林や自然生態系からのカーボンオフセットや、規模的にまだ証明されていない炭素除去技術に依存していることが挙げられます。 一方で、再生可能エネルギーや画期的な技術の可能性は、これまで一貫してモデルの想定を上回っており、太陽光発電量の増加は最も楽観的な予測をも上回っています。2現実的な脱炭素計画と単なる美辞麗句を見極める必要がありますが、クリーンエネルギー革命はここに留まると信じてもよいでしょう。

脱炭素化のためのシナリオ

脱炭素化のシナリオは、いわゆる総合評価モデルから導き出されます。 これらのモデルは気候変動における経済的意思決定や開発と、自然生態系との関連性を把握することを目的としています。 この用語は、シンプルなものから非常に複雑なものまで、多種多様なモデルを表すのに使われています。

一般的にこれらのモデル化されたシナリオは全て、社会的傾向、エネルギー使用の選択肢、技術、および温室効果ガスの排出量を決定するその他の要因をさまざまに組み合わせて使用し、気候システムへの影響をみます。 モデル化されたシナリオの最も重要な違いは、排出量がピークに達する時期、排出が正味ゼロになる時点、炭素除去やその他の技術への依存度に関係しています。

気候システムをモデル化する際の不確実性は相当なものですが、ある種の自然の原理や法則に基づいている限りある程度分かりやすいものです。 一方、人間系のモデルでは、世界がどのように機能し、人口や社会がどのように変化するかについて膨大な数の仮定から始まります。 これらの仮定には、人口増加、経済成長のベースラインケース、資源の利用可能性、技術変化、緩和政策環境などが含まれます。これらの仮定は、社会的行動に関するあらゆる種類の仮定を必要とし、習慣、社会的価値、政局変化、破壊的イノベーションなど、変化の度合いが未知であることに依存します。実際モデルは、相互に作用する様々な要素間のフィードバックやトレードオフを追跡できる限りにおいて、「もしも~したらどうなるだろうか」というような質問をする上で最も有効です。

最もよく知られている脱炭素化シナリオは、気候変動に関する政府間パネル(IPCC)が用いているものです。 IPCCは、2018年に発表した「1.5°Cに関する特別報告書」において、現在の排出レベルからでも、今世紀末までに温暖化を1.5°Cまたは2°C未満に抑えることが出来る道は非常に困難であるが、技術的には実現可能であると結論づけています。3

しかし、10年が経過するごとに課題とコストは増加していきます。排出量削減の開始が遅くなれば、後になって削減量を増やす必要があり、それに伴って2030年から2050年にかけて、付随するコストも高くなります。4 また、排出量のピークが遅くなると、それを補うためにより多くのマイナス排出が必要になります。

大気中のCO2を除去するために、モデルではバイオエネルギーと炭素回収・貯蔵に多く依存することにより、必要なネガティブ・エミッションを実現しています。しかし、ほぼ実証されていないこれらの技術の導入規模は膨大です。2100年までに必要なバイオマス資源作物の栽培にインドの5倍もの面積が必要と割り出したモデルもあれば、5世界の農地の4分の1を必要とするモデルもあります。 こういった規模の土地を別途用意することは、食糧生産のための必要性や所有権の問題、気候変動の影響などを考えると、明らかに実現不可能です。

具体的には、脱炭素に取り組み始めて正味ゼロにならなければならないこと、何等かのマイナス排出が必要になる可能性があり、その規模と性質は関連する選択に依存すること、 そして、世界は、エネルギーの電化を図り、再生可能エネルギーで賄う必要あります。6 また、パリ協定で各国が約束している現在の排出削減量でも、温暖化を2℃以下に抑えることは難しく、公約達成が一年遅れるごとにその影響を回避することがより困難になるという点でもモデルは一致しています。7

IEAレポートのサマリー

IEAは、「Net Zero by 2050」(2050年までにエネルギー関連の二酸化炭素(CO2)排出をネットゼロにするためのロードマップ)と題した227ページにわたるレポートで、経済を支えるエネルギーシステムを全面的に変革し「太陽光や風力などの再生可能エネルギーを主な動力源とする未来」をめざすことを呼びかけています。8 このレポートは、このような変革のために、今後30年間に必要なステップを明らかにしています。重要なのは、このロードマップが2030年までにエネルギーへの公平なアクセスを実現しながら、経済的にも健康面でも同時に重要な利益をもたらすことです。9

IEAのネット・ゼロシナリオでは、再生可能エネルギーを電源とした発電量は2026年(今から4年後)までに石炭を追い抜き、2030年(わずか8年後)までに石油やガスを追い抜きます。2050年には、世界のエネルギー供給の3分の2、発電量の90%近くを再生可能エネルギーが担うべきと説いています。10この再生可能エネルギーへの移行は、運輸、建造物、製造業などの他の分野での電化により補完されなければなりません。

そのためには、2030年に追加される太陽光と風力の容量は2020年に導入された容量の3倍以上でなければなりません。これは気が遠くなるようなことのように聞こえるかもしれませんが、2010年から2020年の間に太陽光と風力の容量はすでに3倍以上に増加しており、多くの新興国では 再生可能エネルギーの拡大に着手したばかりです。11

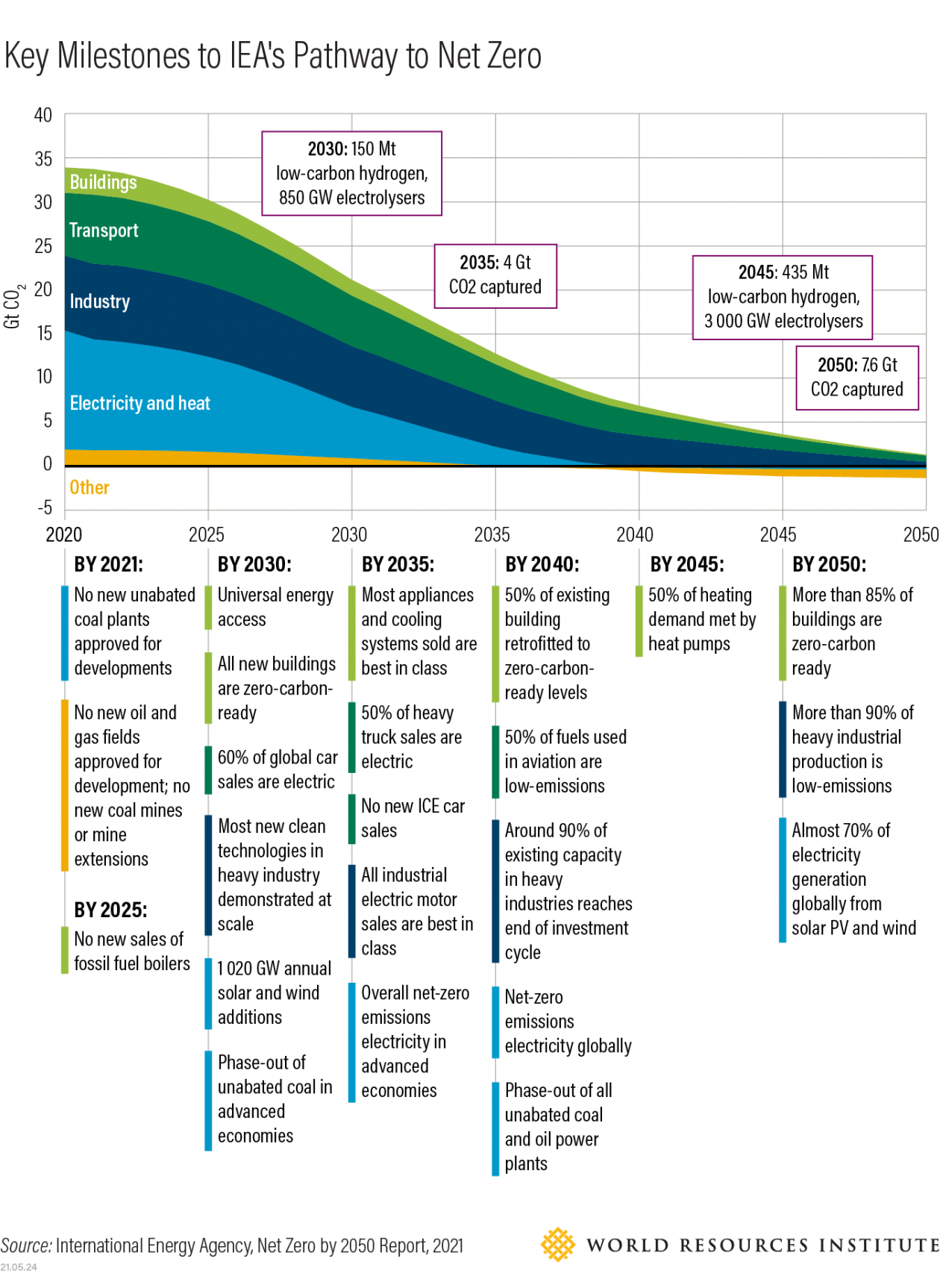

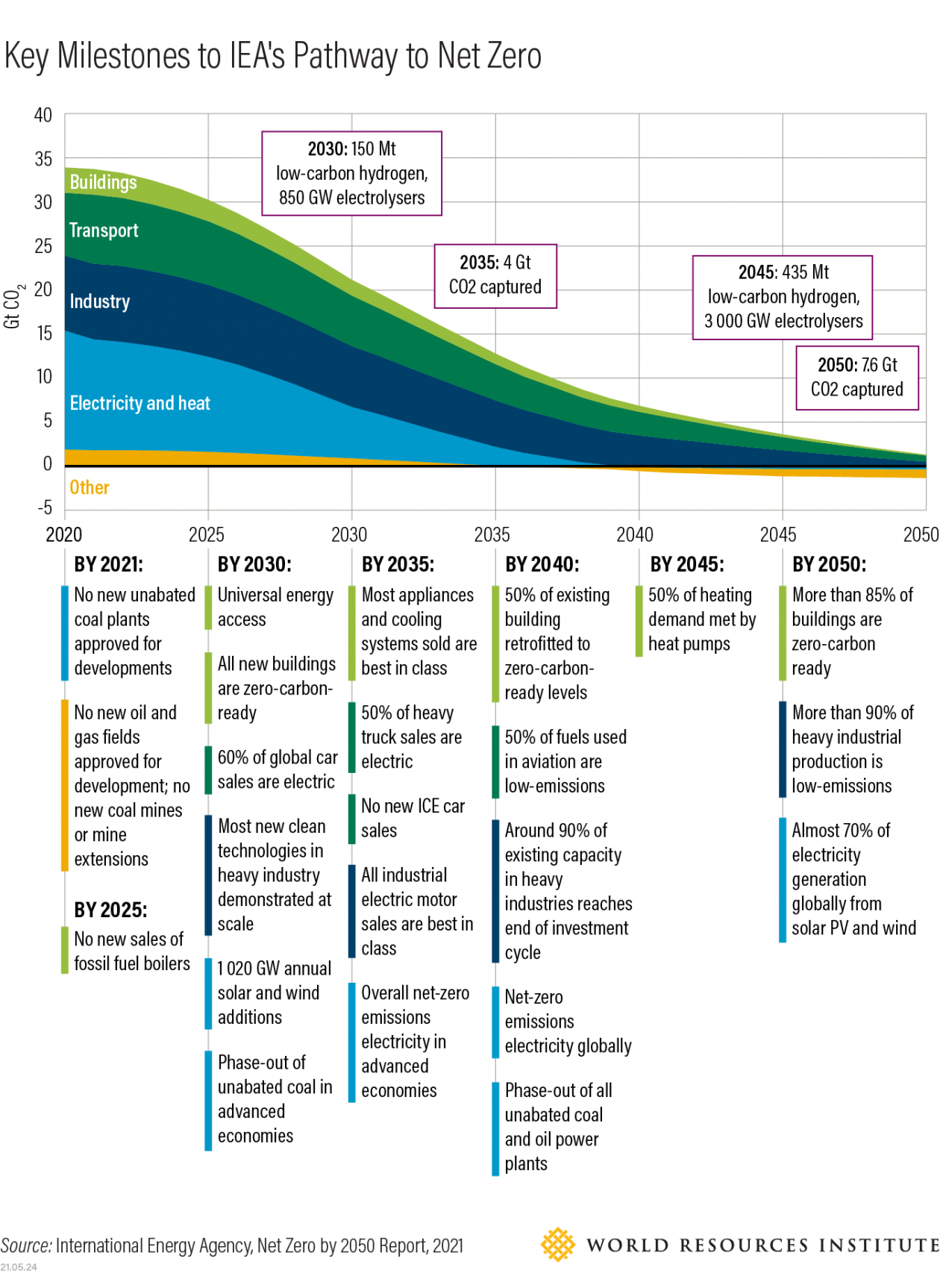

IEAのレポートでは400のマイルストーンが記載されていますが、その中でも重要なゴールポストは、以下の通りです。

• 今年、2021年はすでに開発が決定している油田・ガス田の新規開発を除き、排出物を地下に閉じ込める炭素回収技術を持たない石炭火力発電所の新規開発を各国は承認しません。

• 2025年までには、暖房のための石油やガス炉の新規販売を世界的に禁止し、より環境にやさしい電気式のヒートポンプに置き換えます。

• 2030年までに、世界の新車販売台数の60%を電気自動車は占めるようになるでしょう。(現在は5%のみ) 2035年までには、ガソリンやディーゼルを燃料とする乗用車の新車販売がなくなり、2050年には、世界中で走っているほぼすべての自動車がバッテリーや水素で動くようになります。

• 2035年までに、世界の先進国は発電所からの排出物をゼロにし、風力、太陽光、原子力、低炭素水素などの技術に移行するか、炭素回収を行うことになるでしょう。 そして、2040年までに世界に残るすべての石炭火力発電所を閉鎖するか、炭素回収技術を導入して改修されます。

• 2035年までに、新しい大型トラックの半分以上が電気自動車になります。 2040年までに、持続可能なバイオ燃料や水素燃料など、よりクリーンな代替ジェット燃料が世界中の航空輸送の約半分を占めるようになるでしょう。

[Adapted from IEA by WRI: https://www.wri.org/insights/5-things-know-about-ieas-roadmap-net-zero-2050]

この変化を実現するために、風力や太陽エネルギー、電気自動車など現在利用可能なテクノロジーから始めることができます。 しかし、2050年までには先進的なバッテリー、製鉄所用のよりクリーンな水素燃料、大気中の二酸化炭素を除去する装置など、現在開発中の新技術が排出削減量の約半分を占める必要があります。

これは大規模な変化であることは明らかで、今年から本格的に始める必要があります。 そのためには、クリーンエネルギーとエネルギーインフラへの投資を2030年までに3倍に増やすとともに、研究開発プログラムを大幅に推進し、世界的な協力体制を強化する必要があります。

また、特に重要な金属の調達、労働者のリスキリング、地政学的なパワーの変化など課題がなくなったわけではありません。

幸いなことに、CO2排出量を削減し、再生可能エネルギーに切り替えることで、何百万もの雇用が失われるよりも多く創出されます。12 IEAはこのプロセスにより、世界のGDP成長率はこの10年間で年率0.4%上昇し、2030年には現在のトレンドに比べて4%上昇すると推定しています。 逆に、気候変動の影響を考えると、温暖化を1.5℃から2ºCに抑えることができなければ、2050年までに世界のGDPの約10%が失われる可能性があります。13気候変動政策がもたらす新しい経済によるメリットは、雇用の増加、コスト削減、競争力の向上、新たな市場機会、そして世界中の人々の幸福の向上という点が挙げられます。 そしてこれは技術的にも経済的に実現可能ですが、遅れや失敗の余地はあまりありません。

モデルの限界

シナリオの基本的な問題は、データの収集とシナリオの構築に時間がかかることです。そのため、シナリオは一般的に、今日の開発レベル以前のデータに依存します。これでは エネルギー転換が予想以上の速さで進んでいるため、再生可能エネルギーを含める場合に特に問題となります。モデルが直線的な成長を前提とするする傾向があるため、太陽光、風力発電、リチウムイオン電池のコストが急速に低下している点が反映されにくいことがあります。

逆にモデルの問題点として、回収・貯留やバイオエネルギーなどの関連する炭素除去技術の利用を極端に楽観的に予測していることです。将来のコストが現在よりも大幅に安くなると仮定することで、モデルが炭素除去技術に大きく依存する結果となってしまいます。しかし現実の世界は、モデルのような合理的で最小コストの世界とはまったく異なります。 実際、モデルのもう1つの限界は、政治的制約がないことです。 さらに、モデルでは既存の社会的動向を前提としており、習慣や人間関係が将来も過去と同じであるという想定をしています。1970年代のオイルショックや世界的な紛争からコンピューター、携帯電話、インターネットの台頭に至るまで、ショックやイノベーションといったことを予測することが果たして出来たでしょうか14

さらに重要なことは、ほとんどのモデルが洪水による損失や海面上昇による適応コストなど、気候変動による経済的損害や成長の低下を測定していないため、不作為のコストや行動することによる潜在的なコベネフィットを見逃していることです。

ネット・ゼロ宣言の問題点

一般的には歓迎すべきことですが、今世紀半ばまでに炭素を正味ゼロにするという目標を掲げようとする現在の傾向は、特に森林や炭素吸収生態系からのオフセットを前提としている場合には批判の対象となっています。15これは、今世紀中に気温の上昇や気候変動に伴う害虫や火災の影響を受けて、森林が炭素の吸収源から炭素の供給源に変わることが予想されているためです。 さらに、森林や生態系による自然の炭素吸収は、すでにモデルや脱炭素シナリオ含まれているため、これらの貯留槽を含めることで現在の排出量を補うことができると考えるのは、会計上のトリックにすぎず、 最終的な集計で明らかになることです。16

自然の生態系を保護・強化することは、さまざまな理由から重要ですが、現在の排出量を自然の生態系で賄えると考えるのは危険なことです。例えば、 樹木を植えなければならない規模の計算の中には無意味なものもあります。たとえば、石油・ガスの最大手のシェルは、2030年までにガス生産量を20%増加させる一方で、2050年までにネットゼロにすることを約束していますが、ネットゼロを達成するために、シェルは森林プロジェクトによって排出量を相殺することを期待し、そのためにはブラジルほどの広さの森林が必要になると分析されています。17

自然を利用したソリューションによるオフセットは、排出量の削減に追加して行われるべきであり、代わりに行われるべきではないことは明らかです。二酸化炭素を除去する技術を向上させることは必要ですが、それは農業や航空などの分野で対処が困難な残留排出量を相殺するために用いられるべきです。

しかし、うわべだけの環境保全や抜本的政策が先延ばしにされているにもかかわらず、多くの人がクリーンエネルギー革命は止められないと信じています。 そうでなければ、気候変動の悪影響もすぐに止められなくなってしまうからです。

マリア・グチエレスPh.D.

コンサルタント

サステイナブル・デベロップメント国際研究所 (IISD)

国連気候変動枠組条約(UNFCCC)

訳:伊藤 蛍、笠原 理香

Climate Change – Understanding the Urgency

Part III The road to decarbonization – Summary of “Net Zero by 2050” report by the IEA

Week after week, reports of extreme weather events flood the news. The link between these events and climate change is ever more difficult to question, as their occurrence with such frequency is out of norm with natural variation but instead conforms neatly to predictions of model-run scenarios with increased CO2 concentrations.

And still, emissions continue rising at faster rates. According to the UN, around 789 million people worldwide still have no access to electricity. Hundreds of millions more are expected to further augment their current footprint, with the International Energy Agency (IEA) expecting electricity demand to be 2.5 times today’s levels by 2050.1

Given the unprecedented challenge we face and the small window of opportunity to avoid the worse impacts of climate change, scientists have been busy modeling not only the impacts of climate change according to different CO2 concentrations, but also possible emission scenarios that allow for a relatively good chance of staying below 2° C global mean warming throughout the 21st century. These scenarios generally require total greenhouse gas emissions to peak around 2020-2030 and decrease rapidly to global zero around 2070. Variations to this path have different implications, both in regards to the impacts of climate change, and in terms of the mitigation requirements and associated costs down the line.

Since they form the basis of the choices we are presented with and inform policy decisions, it is helpful to understand decarbonization pathways and the options and trade-offs we face. This essay will therefore provide a quick overview of the basics of scenarios and models, and then focus on the IEA’s influential recently released Net-Zero Report, which is said to present the ‘the most technically feasible, cost-effective and socially acceptable’ path towards decarbonization.

As countries and companies join the current trend and adopt net-zero targets, what follows also touches upon what this might mean – and there’s both cause for concern and for optimism. In brief, the bad news is that many net-zero pledges rely on carbon offsets from forestry and natural ecosystems, which are at best temporary, or on carbon removal technologies, which are still unproven at scale. The good news is that the potential for renewables and breakthrough technologies has thus far consistently surpassed models’ assumptions, the growth of solar blowing past even the most hopeful forecasts. 2 So while we should be cautious and ready to call out the difference between realistic decarbonization plans and mere rhetoric, we can be forgiven for believing the clean energy revolution is here to stay.

Decarbonization scenarios

Decarbonization scenarios are drawn from so-called Integrated assessment models. These models aim to capture the linkages between economic decisions and development and the natural system under climate change. The term is used to describe a large variety of models, from the rather simple to the incredibly complex. In general, they all use different combinations of societal trends, energy use options, technologies and other factors determining greenhouse gas emissions to see their effect on the climate system. The most important variations in the modelled scenarios have to do with the time of peak emission, the point in time at which emissions reach net zero, and their reliance of carbon removal and other technologies.

While the degree of uncertainty when modeling the climate system can be considerable, insofar as it draws on certain natural principles and laws it is somewhat straightforward. In contrast, human systems models start with a long list of assumptions about how the world works and how populations and societies will change. These assumptions include population increase, baseline economic growth, resource availability, technological change, and the mitigation policy environment – which in turn require all kinds of assumptions about social behavior, and depend on changing and unknowable forces, such as habits, social values, political shocks, or disruptive innovation. In fact, models are most useful for asking “what if” questions insofar as they can trace feedback and tradeoffs between different interacting components.

The best-known scenarios are those used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). In its 2018 Special Report on 1.5° C, the IPCC concluded that even from current emission levels, pathways that allow for keeping warming at 1.5° C or below 2° C by the end of the century are extremely challenging but still technically feasible.3

However, with every decade lost, the challenges and costs rise. A slow start in emission reductions needs to be followed by faster reductions later on, with concomitant higher costs for the period 2030–2050. 4 A later peak in emissions peak requires correspondingly more negative emissions to compensate.

To remove CO2 from the atmosphere, models often rely on bioenergy and carbon capture and storage to provide the required negative emissions. The scale of the deployment of these largely unproven technologies is huge. Some model pathways allocate as much as five times the area of India to growing the biomass needed by 2100 5 ; others require a quarter of global agricultural land. Given food production needs, land tenure issues and climate change impacts, it’s clearly not going to happen.

Yet it is not the details but the areas of broad agreement among different models that is most telling: the fact that emissions have to peak and then decline rapidly to net-zero; that negative emissions of some sort are likely to be needed, with their scale and nature depending on related choices; and that the global energy system must be increasingly electrified, sourced

by renewables.6 Models also agree that with the current emission reduction pledges by countries under the Paris Agreement, there is no way we can stay below 2º C of warming, and that for every year of delay, the impacts become more difficult to avoid.7

Enter the IEA

In a 227-page report titled “Net-zero by 2050: A roadmap for the global energy sector,” the IEA calls for a total transformation of the energy systems that underpin our economies towards a future “powered predominantly by renewable energy like solar and wind.”8 The report goes to identify the steps necessary in the next thirty years for such a transformation. Importantly, the roadmap arrives there while simultaneously achieving equitable energy access by 2030 and delivering key economic and health benefits.9

In the IEA net-zero scenario, renewable energy would overtake coal by 2026 (four years from now), and pass oil and gas before 2030 (in only eight years). By 2050, it should go on to meet two-thirds of global energy supply and nearly 90 percent of electricity generation.10 This switch to renewables must be complemented by an electrification process in other sectors such as transportation, buildings and industry to take advantage of the new renewables.

For this to happen, the solar and wind capacity added in 2030 should be more than triple the amount installed in 2020. While this may sound daunting, solar and wind capacity already more than tripled between 2010 and 2020 - and many developing countries are only now starting to scale up to their renewable energy potential.11

The IEA report includes 400 milestones; some of the key goalposts in the scenario include the following:

• This year, 2021, nations would stop approving the development of new oil and gas fields beyond those already committed, as well as any new coal plants unless they include carbon capture technology to trap and bury their emissions underground.

• By 2025, the sale of new oil and gas furnaces to heat buildings would be banned worldwide, to be replaced by cleaner electric heat pumps.

• By 2030, electric vehicles would account for 60 percent of new car sales globally (up from just 5 percent today). By 2035, new gasoline- or diesel-fueled passenger vehicles would no longer be sold, and by 2050, virtually all cars on the roads worldwide would either run on batteries or hydrogen.

• By 2035, the world’s advanced economies would zero out emissions from power plants and shift to technologies like wind, solar, nuclear and low-carbon hydrogen, or use carbon capture. By 2040, all of the world’s remaining coal-fired power plants would be closed or retrofitted with carbon capture technology.

• By 2035, more than half of new heavy trucks would also be electric. By 2040, cleaner alternatives to jet fuel, such as sustainable biofuels or hydrogen, would power roughly half of all air travel worldwide.

[Adapted from IEA by WRI: https://www.wri.org/insights/5-things-know-about-ieas-roadmap-net-zero-2050]

The changes can be started with technologies available today, such as wind and solar energy and electric vehicles. Yet by 2050, new technologies now in development - such as advanced batteries, cleaner hydrogen fuels for steel plants, and devices to pull carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere - would have to account for around half of the emission cuts.

Clearly this is a massive change and it needs to start in earnest this year already. It requires investment in clean energy and energy infrastructure to triple by 2030, as well as a major push in research and development programs and tighter global cooperation.

It also doesn’t come without challenges, particularly those relating to sourcing critical metals, labor force transitions and shifts in geopolitical power.

The good news is that in slashing CO2 emissions and switching to renewable energy many millions more jobs are created than lost.12 The process is estimated by the IEA to be able to lift global GDP growth by 0.4 percent a year over the course of this decade, and 4 percent higher than it would be based on current trends by 2030. Otherwise, given the impacts of climate change, failure to limit warming to 1.5º to 2º C could cost around 10 percent of global GDP by 2050.13 The benefits of a new climate economy – in terms of new jobs, economic savings, competitiveness and market opportunities, as well as improved well-being for people worldwide – are real. And it is technically and economically feasible. There just isn’t much margin for error or delay.

Model limitations

One fundamental problem with scenarios is that data collection and scenario building take time, so scenarios typically rely on data that is behind in terms of real-world developments. This was particularly a problem when including renewables, as the energy transition is happening at a faster than expected rate. The rapid declines in the cost of solar, wind, and lithium-ion batteries have been a challenge to include, as models tend to assume linear growth.

Conversely, models are problematic for their extremely optimistic projections of the use of capture and storage and related carbon removal technologies such as bioenergy, which they tend to rely on heavily partly because they assume “discounting” – assuming near-term costs are higher than those in the future. But the real world is quite unlike the rational, least-cost world of a model. Indeed, another limitation of models is their lack of political constraints. Moreover, because they assume existing societal trends, as if habits and relationships remain the same in the future as in the past, they are unable to forecast shocks or innovations, from the oil crises of the 1970s and global conflicts through to the rise of computers, mobiles and the internet.14

Perhaps more significantly, most models don’t measure economic damages and reduced growth due to climate change, such as flood losses or adaptation costs due to rising sea levels, thus missing the cost of inaction and the potential co-benefits of action.

The problem with some Net-zero pledges

While generally welcome, the current trend to proclaim net-zero carbon targets by mid-century has come under scrutiny, particularly when the plan assumes offsets from forests and carbon-absorbing ecosystems.15 This is because forests are widely expected to turn from a sink of carbon to a source of carbon at some point in this century, affected by rising temperatures as well as pests and fire resulting from climate change. Moreover, natural carbon uptake by forests and ecosystems is already included in the models and decarbonization scenarios, so to assume that current emissions can be compensated for by including these reservoirs amounts to little more than an accounting trick, one that will be all too evident at the final tall16

Protecting and enhancing natural ecosystems is important for all kinds of good reasons, but to assume they will take care of current emissions is a dangerous proposition. Some calculations of the scale at which trees would have to be planted is nonsensical: the oil and gas giant Shell, for example, has committed to net-zero by 2050, while anticipating a 20 percent increase in gas production by 2030. To achieve net-zero, Shell expects to offset its emissions through forest projects, which some analysts calculate would require a forest the size of Brazil.17

It is clear that offsetting with nature-based solutions should be done in addition to reducing emissions, not instead. Improving on techniques for carbon dioxide removal is necessary, but should be used to offset residual, difficult to address emissions in sectors like agriculture and aviation.

Still, in spite of attempts at whitewashing and delaying action, many believe the clean energy revolution will be unstoppable. It better be so, because otherwise the worse impacts of climate change will soon also be unstoppable.

María Gutiérrez, Ph.D.

Consultant

International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD)

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)

1 IEAの「ネット・ゼロシナリオ」についてはこちらをご覧ください See the IEA Net-Zero scenario, at : https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-by-2050.

2 See: https://www.carbonbrief.org/guest-post-why-solar-keeps-being-underestimated

4 https://climateactiontracker.org/global/cat-thermometer/

5 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959378016303399?via%3Dihub

6 温暖化が1.5℃でも2℃であっても排出経路は似ていて、2℃の場合は1.5℃の場合よりもわずかに緩やかで、ネガティブ・エミッションの利用もわずかに少なくなる可能性があります。その違いは、対策が遅れた分気候変動によるインパクトが大きくなり、また対応すべき問題が増えるのです。The path is similar for the 1.5o C and 2o C limits: a soon peak and then rapid decline, just slightly more gradual and with possibly slightly lowered use of negative emissions for 2o C than for 1.5o C. The difference there is the added challenges posed by impacts from climate change itself with delayed action.

7 1.5° C と 2° Cのインパクトの違いについてご理解いただくために、リンク先をご覧ください:To better understand the difference in impacts at 1.5° C and 2° C, see: https://interactive.carbonbrief.org/impacts-climate-change-one-point-five-degrees-two-degrees/?utm_source=web&utm_campaign=Redirect

8 https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-by-2050. IEAは以前から保守的な団体とされ、再生エネルギーの重要性や成長性を軽視することが多くありました(IEAは1970年代の石油ショックに対応して「石油供の安全性を確保する」ために設立されました)。IEAは今回のレポートで、新規油田・ガス田の開発を世界的に即時停止することを求めており、ネット・ゼロ戦略を推進する一方で、油田開発し続けている石油大手会社と対立していますThe IEA has long been seen as a conservative body, and it often downplayed the importance and growth in renewables (it was formed in response to the oil-supply shocks of the 1970s to “ensure the security of oil supplies”). By calling on an immediate worldwide end to approvals of new oil and gas fields, the report places the IEA “at odds with oil giants that are promoting corporate net-zero strategies while continuing to search for more oil.” See: : https://yaleclimateconnections.org/2021/06/key-readings-on-ieas-net-zero-by-2050-report/.

9 IEAの開発ニーズにおけるネット・ゼロシナリオのファクターは、2030年までにユニバーサルな電力アクセスが実現することが重要であり、これは1.5º Cの温暖化に向けたあらゆる(排出)経路がこの要因を含んでいるわけではないからです。The IEA’s net-zero scenario factors in development needs and achieves universal electricity access by 2030, which is important because not all 1.5º C-compatible pathways include this.

10 https://www.carbonbrief.org/iea-renewables-should-overtake-coal-within-five-years-to-secure-1-5c-goal?utm_campaign=Feed%3A%20carbonbrief%20%28The%20Carbon%20Brief%29&utm_content=20210518&utm_medium=feed&utm_source=feedburner

11 IEAは、再生エネルギーの発電コストが低下しているにもかかわらず、その可能性を過小評価していると指摘する声もあります。特に太陽光発電については、過去10年間発電とバッテリーのコストは実際に年率18%で低下していますが、IEAは今後10年間のコスト低下率を5%、2030年以降は2%と想定しています。 Some observers find that the IEA still underestimates the potential of renewables given their reduced costs – especially for solar: while solar and battery costs have been falling at 18 percent a year for the last decade, the IEA assumes a rate of fall of cost of 5 percent over the next decade, and then to 2 percent after 2030). See: :https://reneweconomy.com.au/is-the-iea-still-underestimating-the-growth-of-renewable-energy/

12 IEAとIMF(国際通貨基金)によると、太陽光発電、建築物の効率化、都市交通インフラに100万米ドルを投資するごとに、ガスや石炭に同額を投資した場合の2倍以上の雇用が創出されるといいます。According to the IEA and the International Monetary Fund, each USD $1 million invested in solar photovoltaics, building efficiency or urban transport infrastructure creates more than twice as many jobs as the same amount invested in gas or coal.See: https://www.wri.org/insights/5-things-know-about-ieas-roadmap-net-zero-2050

13 https://www.swissre.com/institute/research/topics-and-risk-dialogues/climate-and-natural-catastrophe-risk/expertise-publication-economics-of-climate-change.html

14経済学的なことをもとにして意思決定するのであれば、これらのモデルは十分に機能し、競争力のある市場で、合理的な参加者たちがいることを前提としています。しかし、ケンブリッジ・エコノメトリックスのヘクター・ポリット氏は、自動車について次のように述べています。「もし誰もがコストの最適化を意識するなら、みんなスマートカーに乗っているはずですが、実際には高急なモデルの車を購入しているのです」と述べています。 (以下リンク先より引用: In using economics as the basis for decision making, models assume fully functioning markets and competitive market behavior as well as rational actors. But as Hector Pollitt, from Cambridge Econometrics, says about cars, “If everyone was cost-optimizing, we’d all be driving Smart cars. But it’s pretty much the opposite of that: many people buy the most expensive model they can” (quoted in: https://www.carbonbrief.org/qa-how-integrated-assessment-models-are-used-to-study-climate-change).

15 例についてはこちらをご覧ください: https://e360.yale.edu/features/net-zero-emissions-winning-strategy-or-destined-for-failure

16 チャタムハウス(英 王立国際問題研究所)のロブ・ベイリー氏は「そもそも、1トンのCO2を排出しない方が、コストやどのくらいの期間、どこでといった不確かな要素ばかりでどんな結果になるかわからないまま、CO2をどれだけ削減できるかと期待しながら排出し続けているよりも、明らかにリスクが少ない」とみています。As Rob Bailey, from Chatham House put it, “It is clearly less risky not to emit a tonne of CO2 in the first place, than to emit one in expectation of being able to sequester it for an unknown period of time, at unknown cost, with unknown consequences, at an unknown date and place in the future.” See: : https://www.carbonbrief.org/in-depth-experts-assess-the-feasibility-of-negative-emissions#bailey

17https://www.climatechangenews.com/2021/05/18/shells-net-zero-plan-will-judged-science-not-spin/